Climate adaptation

COP30 gives adaptation financing a push

Climate adaptation has often been seen as the poorer cousin of climate mitigation.

Measures aimed at helping society prepare better for, and reduce vulnerabilities to, climate impacts are often underinvested. This is as governments and private investors focus more on designing policy and deploying capital towards containing such effects through the reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions.

But that could soon change as the United Nations climate change conference in Belem, Brazil, last year concluded with the aim of tripling adaptation finance to US$120 billion by 2035.

The conference also saw the adoption of 59 adaptation indicators, which would serve as the foundational framework for governments, investors and corporates to start integrating adaptation into their national plans, ESG risk management or investment strategies.

This has led some within the sustainability space to anticipate growing traction for adaptation financing in 2026.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

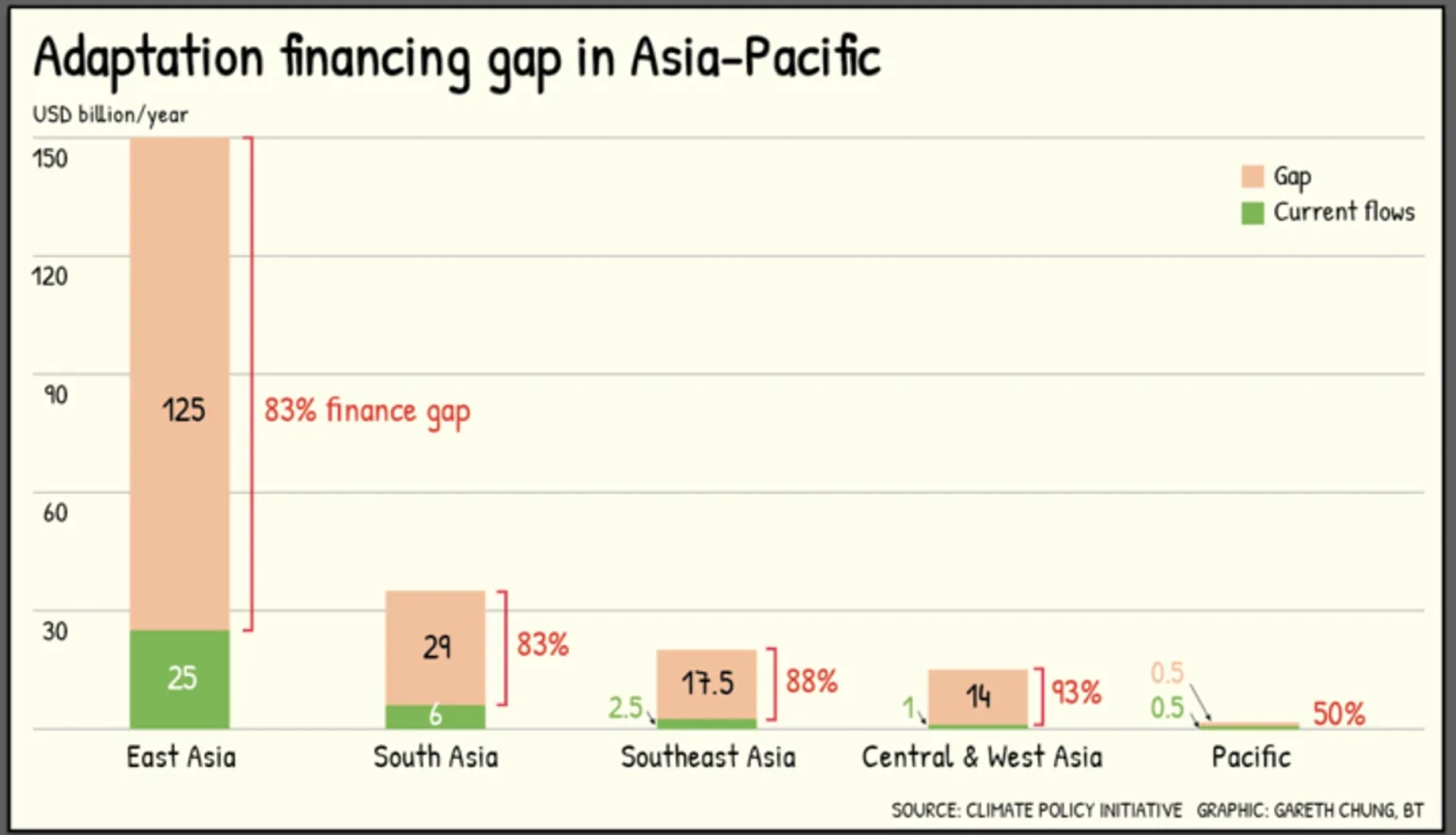

Nonetheless, the US$120 billion target falls far below the amount required to meet the adaptation needs of Asia-Pacific.

According to the Climate Policy Initiative, over US$200 billion is needed every year for Asia-Pacific to maintain climate resilience. However, only about US$34 billion has flowed into the region between 2021 and 2022, leaving an average financing gap of about 83 per cent.

In another report by the Asean Capital Market Forum (ACMF), it cited figures from the Asian Development Bank that US$210 billion of investment was needed annually to build climate-resilient infrastructure in South-east Asia.

All these points to the fact that public funds are not enough to meet the adaptation financing needs of Asia-Pacific, and that private finance needs to plug the gap.

There are early signs that private investors are beginning to pay closer attention.

A recent report by MSCI stated that physical climate risk has become too material to ignore for investors, particularly those with infrastructure assets, as these assets are fixed, long-term and are facing increasing exposure.

They analysed infrastructure-related holdings in 1,427 private-capital funds to estimate potential losses from extreme tropical cyclones, and they found that the probability of severe, value-destroying events within infrastructure portfolios is growing dramatically.

While average losses may rise only 2 per cent by 2050 under a scenario where global warming rises to 3 degree Celsius above industrial levels, the share of assets exposed to catastrophic losses exceeding 20 per cent of their value is projected to increase five-fold — signalling a sharp escalation of tail risk.

Losses could multiply even further in high-risk regions, such as in Asia-Pacific.

MSCI found that constituents in its AC Asia Pacific Infrastructure index – which includes companies that own or operate infrastructure assets across developed and emerging markets in the Asia-Pacific region – were more exposed to potential losses from severe flooding, particularly coastal flooding than their global peers.

On average, infrastructure assets of these constituents could lose up to 19 per cent of their values by 2050 due to asset damage from a severe coastal flooding event, which is higher than the global average of 16 per cent.

If no further efforts are undertaken, such losses could increase by 24 per cent in 2050.

In face of the growing physical climate risks, asset owners are beginning to reassess location risk and adaptation strategy, said MSCI.

Whether Asia-Pacific markets, especially frontier and emerging markets, are able to access this financing is another question.

While demand for adaptation solutions may go up as more investors look to make their assets more climate-resilient, it does not mean that Asia-Pacific, especially frontier and emerging markets, are able to access this financing.

For one, these markets typically lack access to global capital markets and climate funds. Even when they are able to tap on them, they often face higher costs of capital.

Another obstacle is that regulators and the financial sector have not really found a way to make adaptation projects bankable.

While companies producing climate-resilient materials may appear more attractive to investors — as demand for their products is likely to rise with worsening climate impacts — the vast majority of adaptation projects do not generate direct, predictable cash flows.

Projects involving flood barriers, coastal protection or ecosystem restoration often lack clear revenue streams, with benefits accruing to multiple parties rather than a single financier.

There have been some attempts by governments in the region to offer policy levers to improve identification and mobilisation of adaptation activities.

The ACMF report, for example, developed a guide on how the Asean taxonomy can be applied to sectors, activities and investments that are the region’s priorities for addressing climate change adaptation.

However, clearly, more needs to be done among policymakers. To start off, coming up with detailed national adaptation plans that includes information on the climate impacts and vulnerabilities across different sectors in the economy, assessment of present and future physical climate risks, as well as the available investment and financing pathways for adaptation.

Other ESG reads

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.